The importance of male involvement in gender programmes

In the year of the #metoomovement and a week which witnesses both the overturn of the Irish abortion ban and the fourth anniversary of International Menstrual Hygiene Day, it seems a good time to reflect upon the importance of male involvement in gender programmes. This blog focuses on a few of the reasons male involvement is crucial for addressing and challenging the structures and values that underpin gender inequality.

In the last few years, the development community has made several progressive steps towards the inclusion of men as both agents of change and as recipients in gender programming. However, despite this progress male involvement in gender initiatives remains a challenge in practice. There are a small number of men making important contributions to gender equality. However, it is important to recognise that those who don’t acknowledge women and girls as deserving of equal rights, and those who don’t put their belief that women and girls are deserving of equal rights into action, remain a challenge to sustained gender equality.

Why do we need to include boys and men in gender programmes?

There are several reasons why it is crucial for the development community to carefully consider and attempt to integrate male involvement into gender programmes.

The first is related to but goes beyond the issue of semantics. Despite the tendency to be used as such, ‘gender’ is not synonymous with ‘women’. The shift from Women in Development (WID) to Gender and Development (GAD) in the mid-1990’s was a deciding moment in reaching where we are today, as it placed attention squarely upon relations between genders. (Razavi and Miller) Without focusing on gender, development programmes could only achieve limited results as the existing WID paradigm did not adequately encompass the relations and processes which shaped women’s experiences.

A gendered approach crucially means focusing on the day to day relationships between men and women. Neglecting men in gender programmes would be to neglect half of the equation and to undermine the centrality of how relationships between men and women shape ideas and behaviours. Men are gendered beings too (Chant and Gutmann) and their relationship to the structures which pose a challenge to gender equity needs to be addressed in order see both men and women benefit.

Secondly, there is a growing body of literature which suggests that gender programmes have limited impact when they exclude men. Whilst some initiatives merely haven’t succeeded in challenging the structures underlying oppression (Kar), others have actually had adverse effects for their exclusion of men, in some cases resulting in increased violence against women and the restriction of women’s economic freedoms. (UN) Causes have been attributed to the fact that exclusion from such changes can push men into defensive positions in which they seek to reaffirm gendered hierarchies and male authority in the face of threatening changes. This gets to the heart of the issue in highlighting the fact the gender equality is by nature highly radical and highly political.

Genders interact is highly a political manner which is the foundation upon which gender programmes rest. By this, I refer to small p- politics which encompasses the everyday politics of gender interactions. (Cronin Furman et al) Social structures and values which lead to gendered oppression are informed by inherently political relations between genders which makes the involvement of all stakeholders crucial in both dialogue and implementation.

Much of the work towards gender equality involves taking control of one’s rights and realigning structures to distribute power differently. This is an inherently radical and political process which is often met with substantial opposition. In the case of menstruation, deeply embedded cultural and religious taboos can be highly challenging to shift and interventions can be seen as highly threatening to existing norms and hierarchies. Including men in gender programming, for this reason, creates the space for meaningful dialogue and potentially gradual change to structures and views of male privilege.

How do we include boys and men in gender programmes?

The challenge is to find a way that men can be involved in gender programmes in a manner which challenges rather than reinforces ideas and practices of gender inequality. Firstly, there is a need to incorporate an understanding of men as gendered and the relations between men and women as inherently political into programmatic aims and understandings. There is also a need to include men on several different levels of conversation and intervention, ranging from policy making to activism and grassroots campaigning.

The prevailing hierarchies which pose challenges to gender equality are not determined purely by a simple binary informed by gender. Rather by the interaction of gender with other socio-economic identities, including but not exclusive to; sexuality, class, ethnicity, age, and location. (Crenshaw). Effective gender programmes are those which recognise both women and men’s position in society is determined by the interaction between different aspects of their identity. Acknowledging this can help us understand how different men with relative levels of privilege can be integrated at different levels into gender programmes.

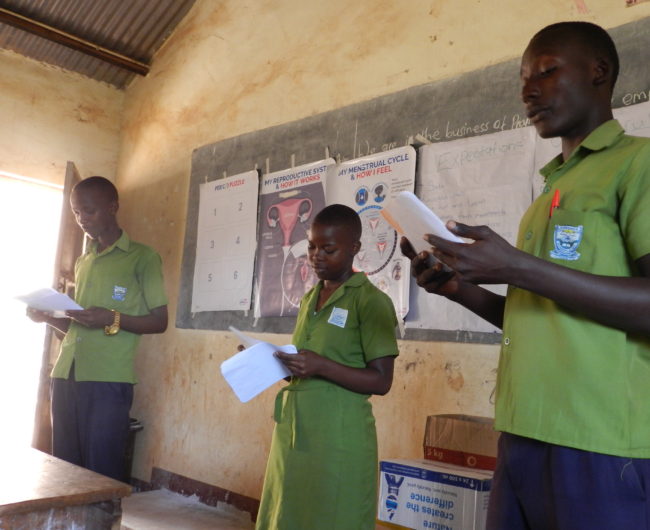

There is also a need to include men in the design and implementation of gender programmes. This will ideally decrease the likelihood of coming up against structures of male privilege and ensure that men have a role to play as changemakers themselves. Behavioural change theory suggests that a ‘diffusion of innovations’ approach can be key to sustained and genuine behavioural and attitudinal change. In this type of model, the participatory engagement of men would be key, with a few initial innovators taking up a changed view or behaviour. This would ideally result in the spreading of the practice to the point of reaching a critical mass. In the context of menstrual health, this might translate to men taking on an awareness-raising role within their community to challenge the stigma surrounding menstruation, or simply creating a supportive and open environment for the women around them. WoMena has developed a detailed male involvement policy which is considered in all projects and activities.

Overall men have a crucial role to play in gender programmes. Their inclusion offers an opportunity to meaningfully challenge existing norms and social structures, whilst at the same time utilising their relative positions of power in a manner which in the long term may contribute significantly towards gender equality.

Blog Author:

Alex Farley

Alex is WoMena’s Research and Project Management Officer and works on the ongoing HIF feasibility assessment of reusable menstrual products in humanitarian programming. She has an MSc in African Development and a research interest in gendered humanitarian programming and policy.

Bibliography:

Chant, S. and Gutmann, M. C. (2015) ‘”Men-streaming” gender? Questions for gender and development policy in the twenty-first century’.

Cornwall, A. and Eade, D. (2011) ‘Deconstructing Development Discourse Buzzwords and Fuzzwords’.

Crenshaw, C. and Crenshaw, K. (1991) ‘Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color’, Stanford Law Review, 43(6), p. 1241.

Cronin-Furman, K., Gowrinathan, N. and Zakaria, R. (2017) ‘Emissaries of Empowerment’.

Dolan, C. (2015) ‘Letting go of the gender binary: Charting new pathways for humanitarian interventions on gender-based violence’, International Review of the Red Cross.

Tripathy, A. and Singh, N. (2015) ‘Putting the men into menstruation: the role of men and boys in community menstrual hygiene management’, 34(1).

Menon, N. (no date) Seeing like a feminist.

Miller, C, and Razavi, S, From WID to GAD: Conceptual Shifts in the Women and Development Discourse, 1995.

Turner, S. (1999) ‘NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Angry young men in camps: gender, age and class relations among Burundian refugees in Tanzania’.

Ward, J. (2016) ‘It’s not about the gender binary, it’s about the gender hierarchy: A reply to Letting Go of the Gender Binary’, International Review of the Red Cross.