Do menstrual cups affect hymens/virginity?

WoMena receives many questions from women and girls, communities and other partners. We review and assemble the best available evidence from academic literature, expert opinion and manufacturer guidelines. We also recognise that there are many unknowns, and that it would be very costly to conduct more robust research. This text was drafted by WoMena’s Knowledge Management Team. Comments by Janie Hampton of the Cup Coalition are gratefully acknowledged.

YOU CAN DOWNLOAD THIS FAQ AS PDF HERE

What is the hymen?

There is widespread belief that girls are born with a solid membrane covering the vaginal opening, and this covering is referred to as a hymen.

In reality, most girls and women do not have a solid membrane covering the vagina. Instead, they have a ring or crescent of thin, elastic mucous membrane folds encircling the entrance of the vagina, with an opening in the middle. The opening allows menstrual blood and vaginal secretions to exit the body.

To reflect the actual physiology, the term vaginal corona was introduced in 2009 by the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU) (Landes 2009). The term is now used by Menstrual Matters, Our bodies Our Selves, International Rescue Committee and others, including by WoMena. Others use ‘hymenal ring’ or ‘hymenal rim’. Still others continue to use the term ‘hymen’ in (NHS). In the following, we will refer to both ‘hymen’ and ‘corona’.

The appearance of the corona varies significantly among individuals in terms of thickness, shape and colour (Magnusson 2009; Hegazy 2012; Our Bodies Ourselves 2014, Jarral 2015, Thomsen & Senderovits 2017, Brochman 2018).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/hymen

The corona changes over time. Berenson et al observe marked changes in the first year after birth (for example from a ring shape to a crescent), then less change at ages 3-9 years (Berenson et 1991, Berenson et al 1992, Berenson 1993). Several researchers note that, in response to the hormones of puberty, the tissue gradually opens and becomes more elastic (Heger 2000, Lahoti 2001, Blank 2008).

Many experts suggest that the corona may become thinner through daily activities, including play, sports, biking, masturbation, fingers inserted with the purpose of virginity testing, medical examination with a speculum, or insertion of tampons or menstrual cups (Goodyear-Smith, 1998, Curtis 1999, Adams 2004, Blank 2008, Magnusson 2009, Smith 2011, Our Bodies Ourselves 2014, Brochmann & Dahl 2018). However, although this seems plausible, there is little research to describe what actually happens. Some studies find little evidence that, for example, tampon use changes the appearance of the corona (Emans 1994, Loeber 2008). Price finds major changes happening only as a result of severe injury (Price, 2013).

We could find no studies examining whether menstrual cup use affects the appearance or structure of the corona.

Though the vast majority of women have physiological ‘normal’ variations of the corona, some are considered pathological. The variant that most closely reflects the popular understanding of the hymen as a membrane fully covering the vagina is referred to as an ‘imperforate hymen.’ It is extremely rare, estimated by Lardenoije to occur in 0.05% of girls, and needs to be surgically opened to allow for vaginal secretions, including menstrual blood, to exit the body (Lardenoije 2009, Our Bodies Our Selves 2014, Fahmy 2015).

What are virginity tests, and are they accurate or acceptable?

There is widespread belief that the status of the hymen can be identified through physical or visual examination, and that the structure of the hymen corresponds to a woman’s virginity.

Therefore, in order to judge whether a girl or a woman is a virgin, some use ‘virginity tests’, in the form of visual inspection of the vagina, or physical examination, digitally probing it by inserting two fingers into the vagina (the ‘two-finger test’) (Brulliard, 2009, WHO 2018).

However, scientific literature to date concludes that inspection is neither sensitive nor specific. Some women who have never had vaginal intercourse may have little or no visible corona. Others who have had vaginal intercourse may still have a non-disrupted, visible corona (Rogers 1998). One study found that women aged 13-19 years who reported past vaginal intercourse still had intact hymens in 52% of cases (Adams et al 2004). Further, a torn hymen may heal without any visible scarring (McCann 2007). A systematic review of 17 studies of virginity tests found that examination did not serve as a reliable indicator of virginity. The review also found that these examinations could cause physical and emotional harm to the individual being examined (Olson and Garcia-Moreno 2017). Forensic experts confirm this finding (Independent Forensic Expert Group, 2015, Thomsen and Senderovitz 2017).

In 2014, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and the Committee on the Rights of the Child released a Joint Recommendation which referred to virginity tests as a “harmful practice” (United Nations 2014). Organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have also condemned the use of virginity tests. Human Rights Watch declared virginity tests to be “unscientific, inhuman, and degrading,” decrying their use in countries such as India and Indonesia (Human Rights Watch 2010; Human Rights Watch 2017). Amnesty International argues that forced virginity testing, as performed by soldiers on female protesters in Egypt during the uprising in 2011, constitutes torture (Trimel 2011).

Since 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that no health care providers should perform virginity tests since they have no scientific validity (WHO 2014), and in October 2018, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UN Women and WHO jointly spoke out against virginity testing (WHO 2018).

Several countries have outlawed such tests, including Afghanistan, where Human Rights Watch reported that 95% of girls in juvenile detention were accused of ‘moral crimes’ and were subjected to virginity testing (Human Rights Watch 2016, Kelly, 2018). It is not clear what effect the change in legal status has had.

Do all girls or women bleed at first sexual intercourse?

There is widespread belief that the hymen is always ruptured at first vaginal sexual intercourse, causing bleeding.

In fact, there is very little peer-reviewed research to describe bleeding at first vaginal intercourse, and studies rely on reports by women of their past experience. One often-quoted estimate comes from an informal survey of 41 medical workers in the UK, of whom 14 (34%) bled at first intercourse, 26 (63%) did not, and one could not remember (Paterson-Brown 1998). Another equally informal estimate is that less than half bleed during first vaginal sexual intercourse (Thomsen and Senderovitz 2017). Loeber, in a study of 487 women from different cultural backgrounds in the Netherlands, found that 59.7% of women with Dutch background reported no blood loss at first intercourse, compared to 26.0% of women with Middle Eastern and Moroccan background. There was no correlation between age at first intercourse and bleeding among the Dutch women. However, women who were not Dutch reported increased blood loss with increasing age at first intercourse. Loeber hypothesizes that this could be explained by increasing expectation of blood loss, or fear of first coitus (Loeber 2008).

Vaginal bleeding is not restricted to first sexual intercourse. It may occur more than once throughout the lifespan (Boukhanni et al 2016), and post-coital bleeding is a frequent health complaint for sexually active women (Dubuisson 2013).

Some experts link bleeding and pain, proposing that both the amount of pain and bleeding depend on the type of intercourse: early, hurried and forceful intercourse may be more likely to cause bleeding (Our Bodies Ourselves 2014; Brochmann & Dahl, 2018, NHS 2018). Here again, although this seems plausible, there is little evidence. Loeber found that women with Dutch background reported lower levels of severe pain at first intercourse than others (e.g. African women 49%, Dutch 19%), and also lower levels of bleeding. However, levels of reported pain vary, and pain may be difficult to define. In a study of young Swedish women, 65% reported pain related to first sexual intercourse (Elmerstig 2009).

If vaginal bleeding is not a reliable marker of first vaginal intercourse, why is it so widely believed and reported that bleeding always occurs the first time a woman has vaginal intercourse? There is much anecdotal evidence of how girls and women ensure that there is an appearance of bleeding. For example that women, helped by their mothers, sharpen their nails to be able to scratch their skin and cause bleeding, or bring a container of chicken blood for their wedding night to ensure the presence of blood and to prove premarital virginity. There are also many reports of women seeking surgery to restore the hymen, and that medical doctors may face ethical dilemmas in deciding whether or not to perform such surgery (Brochmann & Dahl, 2018; Leye et al 2018). Private companies, such as one in Hong Kong, have identified a market for the sale of fake hymens ‘for the purpose of simulating an intact human hymen’. The product is inserted into the vagina and bleeds fake blood during sexual intercourse, giving the impression that the woman is a virgin. (Hymenshop, accessed Sept 2018).

What is ‘virginity’? What are religious and cultural views?

There is widespread belief that an absence of vaginal bleeding following intercourse on the wedding night proves the bride is not a virgin.

However, how an individual or community defines virginity, or the ‘loss’ of it, is highly personal and specific to both family and community. As described above, virginity cannot be determined or proven by physical appearance, physical exam, or bleeding at first sexual intercourse. Virginity typically refers to not having had penile, penetrative vaginal intercourse, but the definition is not always clear-cut, including the definition of penetration (Anderst et al 1991). Indeed, when WoMena trainers ask community members about the definition of ‘virginity’, responses vary widely, for example ‘someone who has not yet had a child’.

If virginity is understood as penile, penetrative vaginal intercourse, the use of a menstrual cup or tampon does not affect virginity. Along with other daily activities, using a menstrual cup or tampon may or may not cause the corona to stretch, but that would not constitute ‘loss’ of virginity.

Virginity before marriage is a deep concern and interest in many religions and cultures. It is beyond the scope of this factsheet to present a full review of religious and cultural views regarding virginity, but we have consulted religious leaders and community members of different faiths.

These religious leaders are aware that there are many different interpretations of sacred texts. They are generally quite aware that the hymen is not necessarily intact at first vaginal intercourse, that it may vary in form, and that it may be affected by daily activities as described above. They agree that virginity is only ‘lost’ after penile penetrative vaginal intercourse. Some of them (from a variety of religions) are aware of the updated understanding of the physiology of the ‘hymen’, and refer to the vaginal corona instead.

UN organizations (UN OHCHR, UNWomen and WHO) note that ‘the term “virginity” is not a medical or scientific term. Rather, the concept of “virginity” is a social, cultural and religious construct – one that reflects gender discrimination against women and girls’ (WHO, 2018). For example, when virginity is narrowly defined to only include penetrative vaginal intercourse, and there is social pressure to maintain virginity before marriage, young women may inadvertently be encouraged to engage in other sexual acts that carry greater health risks, such as unprotected penetrative anal intercourse. Several authors identify the emphasis on virginity as a cultural suppression of females, including in ‘modern’ societies such as the United States (Educational Publishing Foundation, 2002, Valenti 2009).

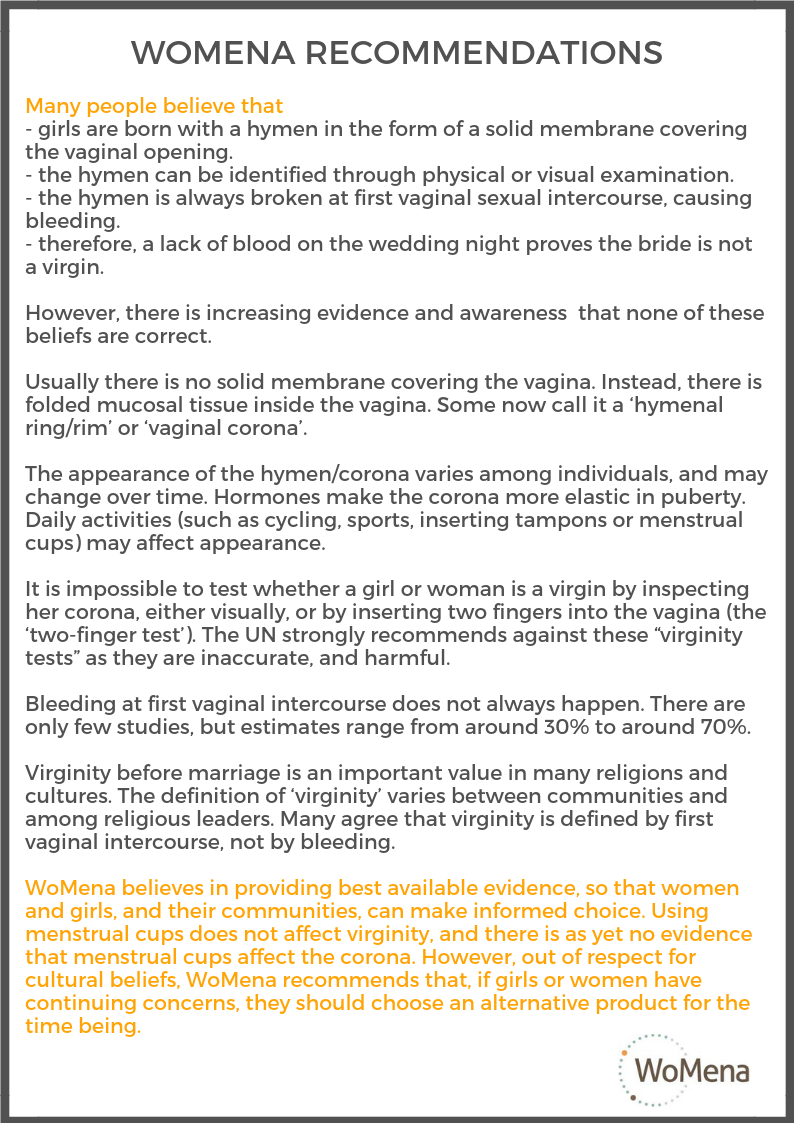

WoMena Recommendation

WoMena strongly believes in giving the best possible knowledge to girls, women and community leaders so that they can empower themselves to make informed choices. We therefore aim to present the best available evidence. In our experience, girls and women, community and religious leaders alike are interested in learning more about menstruation, menstrual cups and virginity, and are reassured that cups are acceptable once they have the best available knowledge.

WoMena respects that, if girls and women continue have continuing concerns, they should choose an alternative product for the time being. Producers of menstrual cups such as Ruby Cups agree (RubyCups 2017, ReCircleCup undated).

Clearly, more research is needed in this area. Some pertinent questions include:

- How do individuals and societies understand virginity?

- How many girls and women from different societies report bleeding at first intercourse?

- If research confirms that a minority of women experience post-coital bleeding at first intercourse, how and why has the ‘myth’ been maintained for so long?

- To what extent is there a combined belief in a ‘hymen’ as a solid covering, bleeding and pain at first sexual intercourse, and how does that affect perceptions?

- How meaningful is scientific knowledge in changing perceptions and cultural understandings?

- What are the most effective methods of sharing clear and scientific information with adolescents, their parents and teachers?

- How can opinion formers such as parents, teachers and religious and community leaders be helped to share correct information?

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME BELOW!

REFERENCES:

Adams, Joyce A., et al. “Differences in Hymenal Morphology between Adolescent Girls with and without a History of Consensual Sexual Intercourse.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 158, no. 3, Mar. 2004, pp. 280–85. PubMed, doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.3.280.

Anderst, J, et al (1991)Reports of repetitive penile-genital penetration often have no definitive evidence of penetration. Pediatrics. 2009 Sep;124(3):e403-9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3053. Epub 2009 Aug 3.

Berenson A, Heger A, Andrews S. Appearance of the hymen in newborns. Pediatrics. 1991;87(4):458-65.

Berenson, A. B. et al. (1992) ‘Appearance of the Hymen in Prepubertal Girls’, Pediatrics, 89(3), p. 387 LP-394. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/89/3/387.

Berenson AB. Appearance of the hymen at birth and one year of age: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1993;91(4):820-5.

Blank, Hanne (2008). Virgin: The Untouched History. Bloomsbury USA. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-59691-011-9.

Boukhanni L, Dhibou H, Zilfi W, Housseini KI, Benkeddour YA, Aboulfalah A, Asmouki H, Soummani A (2016). ‘Postcoital bleeding: 68 case-reports and review of the literature’ (artile in French). Pan Afr Med J. ;23:131. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.131.9073.

Brochmann Nina Dølvik, Ellen Stokken Dahl, Lucy Moffatt (2018), ‘The wonder down under – a user’s guide to the vagina’, Yellow Kite.

Brochmann Nina Dølvik, Ellen Stokken Dahl (2017). ‘The virginity fraud’ TEDxOslo 2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fBQnQTkhsq4

Brulliard, Karin (26 September 2008). “Zulus Eagerly Defy Ban on Virginity Test”. The Washington Post. NONGOMA, South Africa. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

Curtis Emma, Camille San Lazaro (1999). “Appearance of the hymen in adolescents is not well documented” (PDF). BMJ : British Medical Journal. 318(7183).

Dubuisson J, Boukrid M, Petignat P. (2013) Management of post-coital bleeding: should all women be referred?. Rev Med Suisse. 2013 Oct 23;9(403):1933-4, 1936-7. Article in French

Educational Publishing Foundation, Review of General Psychology (2002), Vol. 6, No. 2, 166 –203: Cultural Suppression of Female Sexuality

Elmerstig, E, Wilma B Swahnberg (2009) Young Swedish women’s experience of pain and discomfort during sexual intercourse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 88(1):98-103. doi: 10.1080/00016340802620999.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19140047#

Emans, S. Jean, et al. “Hymenal Findings in Adolescent Women: Impact of Tampon Use and Consensual Sexual Activity.” The Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 125, no. 1, July 1994, pp. 153–60. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70144-X.

Fahmy, M. A. B. (2015) ‘Hymen’, in Rare Congenital Genitourinary Anomalies: An Illustrated Reference Guide. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 159–170. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43680-6_10.

Goodyear-Smith FA; Laidlaw TM. (1998) Can tampon use cause hymen changes in girls who have not had sexual intercourse? A review of the literature. [Review] [29 refs] Forensic Science International. 94(1-2):1473

Hagstad AJ 1990 Mödom -mest myt (Maidenhood–mostly a myth) Lakartidningen. 1990 Sep 12;87(37):2857-8. [Article in Swedish]

Hegazy, Abdelmonem A, Al-Rukban MO: Hymen: facts and conceptions, 2012, theHealth | Volume 3 | Issue 4

Heger, Astrid H.; Emans, S. Jean, eds. (2000). Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas (PDF) (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780195074253.

Human Rights Watch. ‘Afghanistan: ‘End ‘Moral Crimes’ Charges, ‘Virginity’ Tests’. 25 May 2016

https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/05/25/afghanistan-end-moral-crimes-charges-virginity-tests

Human Rights Watch. “Indonesia: No End to Abusive ‘Virginity Tests.’” Human Rights Watch, 22 Nov. 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/11/22/indonesia-no-end-abusive-virginity-tests.

Human Rights Watch. Dignity on Trial | India’s Need for Sound Standards for Conducting and Interpreting Forensic Examinations of Rape Survivors. Human Rights Watch, 2010, p. 59, https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/09/06/dignity-trial/indias-need-sound-standards-conducting-and-interpreting-forensic.

Hymenshop: http://www.hymenshop.com/, retrieved 3 Oct 2018)

Independent Forensic Expert Group, 2015. ‘Statement on virginity testing’, Journal of Forensic & Legal Medicine, 33. 121-124.

Jarral Farrah (2015) A Hymen Epiphany J Clin Ethics. 26(2):158-60.

Kelly, A. (2018, July 5). Breakthrough made in fight to end virginity testing in Afghanistan. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jul/05/breakthrough-fight-to-end-virginity-testing-afghanistan

Khan, Mohammed. Interpretation of statements about the hymen in the Koran or by religious scholars. E-mail correspondance. 2018

Knight, Bernard (1997). Simpson’s Forensic Medicine (11th ed.). London: Arnold. p. 114. ISBN 0-7131-4452-1

Lahoti, Sheela L.; McClain, Natalie; Girardet, Rebecca; McNeese, Margaret; Cheung, Kim (2001-03-01). “Evaluating the Child for Sexual Abuse”. American Family Physician. 63 (5). ISSN 0002-838X.

Landes, David. “Swedish Group Renames Hymen ‘Vaginal Corona.’” The Local, 8 Dec. 2009, https://www.thelocal.se/20091208/23720.

Lardenoije Céline , Robert Aardenburg, and Helen Mertens (2009) Imperforate hymen: a cause of abdominal pain in female adolescents BMJ Case Rep doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0722

Leye E, Ogbe E, Heyerick M. ‘Doing hymen reconstruction’: an analysis of perceptions and experiences of Flemish gynaecologists. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):91.

Loeber, Olga (2008). “Over het zwaard en de schede; bloedverlies en pijn bij de eerste coïtus Een onderzoek bij vrouwen uit diverse culturen” (On the sword and the sheath: blood loss and pain at first coitus – a study of women from different cultures). Tijdschrift voor Seksuologie (in Dutch). 32. pp. 129–137. (In Dutch)

Magnusson, Anna Knöfel. Vaginal Corona: Myths Surrounding Virginity – Your Questions Answered. Translated by Jonas Hartelius, Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU), 2009, p. 22, https://www.rfsu.se/globalassets/pdf/vaginal-corona-english.pdf.

McCann, Miyamoto, Boyle & Rogers, 2007. ‘Healing of hymenal injuries in prepubertal and adolescent girls: a descriptive study,’ Pediatrics, 119-(5) 1094-1106.

Menstrual Matters (by Sally King) https://www.menstrual-matters.com/blog/virginity-myth/ retrieved 3 Oct 2018)

National Health Service (NHS): ‘Does a woman always bleed when she has sex for the first time?’https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/sexual-health/does-a-woman-always-bleed-when-she-has-sex-for-the-first-time/ Accessed 2018.09.16

National Health Service (NHS): Girls’ bodies Q&A: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/sexual-health/girls-bodies-faqs/ Accessed 20180926

Olson, Rose McKeon, and Claudia García-Moreno. “Virginity Testing: A Systematic Review.” Reproductive Health, vol. 14, May 2017. PubMed Central, doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0319-0.

Our Bodies Ourselves, “Renaming the Hymen: Vaginal Corona.” https://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/health-info/renaming-the-hymen-vaginal-corona/. Accessed 30 May 2018

Paterson-Brown, Sara. “Commentary: Education about the Hymen Is Needed.” BMJ : British Medical Journal; London, vol. 316, no. 7129, Feb. 1998, p. 461. ProQuest, https://www.bmj.com/content/316/7129/461.full

Price J. (2013) Injuries in prepubertal and pubertal girls. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. Feb;27(1):131-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.008.

Rogers, Deborah J; Stark, Margaret (1998-08-08). “The hymen is not necessarily torn after sexual intercourse”. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 317 (7155): 414. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1113684. PMID 9694770.

ReCircleCup (undated) Why Using a Menstrual Cup Won’t Make You Lose Your Virginity https://www.recircle.life/menstrual-cup-virginity (recircleCup)Ruby Cup Press release 28 March 2017 http://rubycup.com/blog/hymens-virginity-and-menstrual-cups-in-east-africa/

Smith A 2011, ‘The prepubertal hymen’. Australian Family Physician, 40 (11):873

Thomsen, Jørgen Lange, and Gry Stevens Senderovitz. Mødommen (the hymen). Gyldendal, 2017.

Trimel, Suzanne. “Amnesty International Demands Justice in Forced ‘Virginity Tests’ in Egypt.” Amnesty International USA, 2011, https://www.amnestyusa.org/press-releases/amnesty-international-demands-justice-in-forced-virginity-tests-in-egypt/.

United Nations. Joint General Recommendation No. 31 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women/General Comment No. 18 of the Committee of the Rights of the Child on Harmful Practices. United Nations, 2014, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N14/627/78/PDF/N1462778.pdf?OpenElement.

Valenti, Jessica. 2009. “The Purity Myth – How America’s obsession with virginity is hurting young women” Seal Press

World Health Organization. Health Care for Women Subjected to Intimate Partner Violence or Sexual Violence: A Clinical Handbook. 14.26, World Health Organization, 2014, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136101/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf;jsessionid=BDE1B75A621EB8F27019E0EA4D144AA6?sequence=1.

World Health Organization: Press release 17 October 2018: United Nations agencies call for ban on virginity testing http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/17-10-2018-united-nations-agencies-call-for-ban-on-virginity-testing